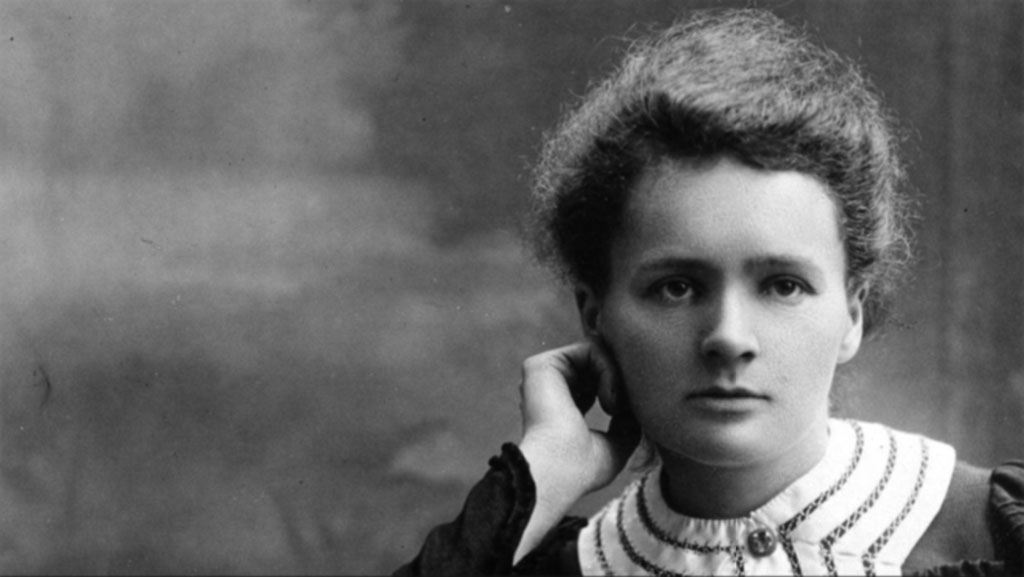

Marie Curie, Female Scientist Extraordinaire

Contributed by

Arlene Lagman

January 24, 2016

Contributed by

Arlene Lagman

January 24, 2016

Many people consider Marie Curie the best known and most inspirational woman of science. Her amazing contributions to the field were backed by a life that was a perfect example of dedication to personal passions motivated by the desire to help humankind.

Born in Warsaw, Poland in 1867, Maria Salomea Sklodowska was the youngest of five children. The Sklodowska family, who once lived a comfortable life, lost most of their property and finances due to the uprisings that overwhelmed Poland a few years before she was born. Maria’s family not only struggled to make ends meet but also had to deal with tragedies early on in their family life. In 1878, her mother died from tuberculosis when Maria was just ten years old. This came three years after the family dealt with their first tragedy, which was the death of Zofia (Maria’s oldest sibling) due to typhus.

These two deaths in their family prompted Maria to turn agnostic, despite growing up with a devoutly Catholic mother.

Maria was only sixteen years old when she received her first significant academic accolade: a gold medal upon her graduation in 1883. She took the year off soon after to stay with relatives in the countryside so that she could heal from a collapse, which many pinpoint was due to depression.

In those times, women were not permitted to study in regular institutions of higher learning. So, together with her sister Bronislawa, she instead opted to go with the underground Flying University, which was the only Polish institution that accepted female students.

As money was still tight, Maria took a job first as a tutor and then as a governess for a family of a distant relative, the Zorawskis. There, she fell in love with Kazimierz Zorawski, the son who would later become a renowned mathematician. As she was poor, the parents of Kazimierz rejected the relationship.

In the early 1890s, Maria focused her efforts on earning enough funds to pay for further education in Paris, to where her sister had moved. She also busied herself by learning from a tutor and self-studying. It was also during this time that she embarked on her life-long training in science, beginning in a chemical laboratory in Warsaw.

In the latter part of 1891, Maria left for France and lived with her sister before securing quarters of her own near the University of Paris, which was where she pursued studies in mathematics, chemistry, and physics. Maria, who then became known as Marie (as is the French counterpart of her name), struggled for resources and had occasional fainting spells from lack of sustenance. Still, she kept to her studies during the day and earned a little during the evenings through tutoring work. Finally, in 1893, she obtained a physics degree and began working for Professor Gabriel Lippmann in his industrial laboratory. At this time, she pursued another degree at the same university a mere year after.

Marie’s scientific career benefited from opportunities to engage in experimentation and research through commissioned work from both the private and public spheres. It was also during these early years that she met and fell in love with Pierre Curie, a fellow physicist and instructor at the School of Physics and Chemistry in France.

Pierre proposed marriage and Marie only agreed after a visit to Poland. She went back to Poland with the intent to pursue her work in the academe in her native country but it yielded no success simply because she was female. Pierre and Marie were married on July 26, 1895, and apart from their passion for science, they spent ample time on shared pursuits, such as trips abroad and long bicycle rides together. The Curies were blessed with two daughters, Irene and Eve. The couple frequently collaborated on scientific pursuits together in their makeshift laboratory and, among their other accomplishments, are credited for the discovery of element radioactivity, and the new elements “polonium” (named after her native Poland) and “radium” (Latin for “ray”). The husband-and-wife team published 32 scientific papers from 1898 to 1902, which included one that identified that tumor cells are quickly destroyed with radium exposure.

Pierre tragically died on April 19, 1906 in a road accident, which left Marie devastated. But despite yet another loss, she still forged ahead with her academic and scientific pursuits. In the same year, she accepted, on behalf of her husband, a professorial chair at the University of Paris, making her the first female professor of the esteemed university.

Marie Curie became the first female faculty member at Ecole Normale Superieure in 1900. She obtained her doctorate degree in 1903 from the University of Paris.

She received two Nobel Prizes – in 1903 for physics, and in 1911 for chemistry. She is the first female recipient of the Nobel Prize, the first person and only woman to have prizes in two fields, and the only person to ever win in multiple sciences.

She also received the following awards: the Davy Medal (1903), Matteucci Medal (1904), Actonian Prize (1907) and the Elliot Cresson Medal (1909).

Being a female in Marie Curie’s lifetime and chosen field often meant inequality. She was initially supposed to be kept out of the Nobel Prize honor until her husband found out and issued a complaint. She was not permitted to speak at a radioactivity lecture at the Royal Institution in London because she was a woman. She was forced to be very thorough in outlining her significant contributions to papers she pushed, as not doing so could result in repercussions in the acknowledgment of her work and originality. Marie was bypassed for an election to the French Academy of Sciences in 1911 in favor of Edouard Branly, the inventor who assisted in the creation of the wireless telegraph.

Her personal life was also challenging due to her success as a female scientist. The media did not spare her; using her lack of religion and foreign status as excuses to criticize her and creating false stories that she was Jewish. A relationship she had developed with physicist Paul Langevin in 1910 to 1911 was branded a scandal due to Langevin being a man whose wedding was on the rocks, and quite possibly because she was five years his senior. A mob had formed in front of her home, accusing her of being a Jewish home-wrecking foreigner. Marie, together with her daughters, had no choice but to seek refuge in a friend’s home.

Despite the attention from the scientific community and the world, Marie usually preferred to stay out of the limelight unless she had to generate funds to further her research. She (and also Pierre) did not patent their important discoveries so that research on these by other scientists could continue freely. She was known to the donate money she had received from her work in science to friends, family members, and the needy.

During World War 1, she designed and created mobile x-ray machines that helped front-line medical officers treat the wounded, using her own supply of radium. An estimated one million soldiers benefitted from her invention. She trained more than 200 women to become medical aides.

Marie even went as far as trying to donate her Nobel gold to the war effort, which was declined by the government. Unfazed, she instead purchased war bonds and used her Nobel Prize money to do so. Despite these humanitarian efforts, Marie Curie never received any recognition from the French government.

Marie Curie spent her post-war years touring various countries to deliver lectures and raise funds for various research efforts on radium. She had travelled to the United States, Brazil, Spain, Belgium, and Czechoslovakia. She became a member and fellow of many important research institutes and international commissions.

On July 4, 1934, Marie Curie died from aplastic anemia in Sancellemoz Sanatorium. Her cause of death was believed to be due to her long-spanning exposure to radiation. Her remains, and those of her husband Pierre, were relocated to the Pantheon in Paris as a way of honoring their achievements in the field of science.

Marie Curie’s tireless and groundbreaking scientific work, conducted from within a prejudiced and patriarchic culture has made her a woman to look up to. Her achievements have shaped society, saved millions of lives, and became the entry points for even more groundbreaking work in the fields of science and medicine.

—

We are the leaders, innovators, and visionaries – whether in the public eye or behind the scenes – who are revolutionizing the way people think and live. We are #ConnectedWomen.

Join the Connected Women community now, it’s free!

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.